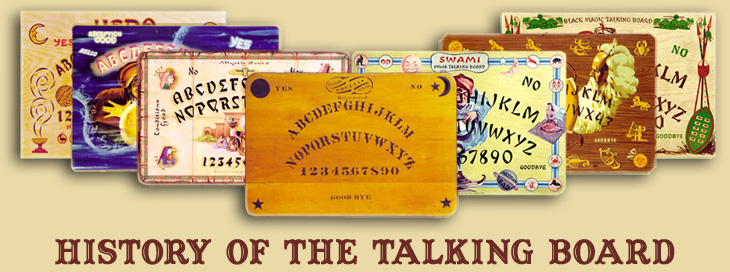

In the year 1848, something unusual happened in a Hydesville, New York cabin. Two sisters, Margaret and Kate Fox, contacted the spirit of a dead peddler, became instant celebrities, and sparked a national obsession that spread all across the United States and Europe. It was the birth of modern Spiritualism.

The whole world, it seemed, was ripe for communication with the dead. Spiritualist churches sprang up everywhere and persons with the special gift or "pipeline" to the "other side" were in great demand. These unique individuals, designated "mediums" because they acted as intermediaries between spirits and humans, invented a variety of interesting ways to communicate with the spirit world. Table turning (tilting or tipping) was one of these. The medium and attending sitters would rest their fingers lightly on a table and wait for spiritual contact. Soon, the table would tilt and move, and knock on the floor to letters called from the alphabet. Entire messages from the spirits were spelled out in this way.

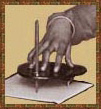

A less noisy technique was a form of spirit writing using a small basket with a pencil attached to one end. The medium simply had to touch the basket, establish contact, and the spirit would take over, writing the message from the Great Beyond. This pencil basket evolved into the heart-shaped planchette, a more sophisticated tool with two rotating casters underneath and a pencil at the tip, forming the third leg. Spiritualists immediately discovered that in addition to writing messages, the planchette could perform as a pointer, setting the stage for the talking boards to come. Kate Field wrote, "Major W. wished to be told his wife's name, and presented me with a list of thirteen names. After three attempts, Planchette pointed out the correct one." —Planchette's Diary, 1868. According to some writers, the inventor of the planchette was a well-known French medium named M. Planchette. This is unlikely considering that no information on this individual exists and that the French word "planchette" translates to English as "little plank."

The problem with table turning was that it

took far too long to spell out messages. Sitters

became bored when the novelty of a rocking table

wore off and the chore of interpreting knocks

began. Planchette writing was often difficult or

impossible to read. It was a challenge just keeping

the instrument centered on the paper long enough to

get a decipherable message. Consequently, many

mediums dispensed with the spiritual apparatuses

altogether, preferring to transmit from the spirit

world mentally in an altered state of consciousness

called "trance." Others eliminated the planchette

but kept the pencil, finding the hand a more

precise and less troublesome writing instrument.

But there were also those who felt it crucial to

use the right equipment if they were going to

contact the spirit world properly. These

resourceful individuals built weird alphanumeric

gadgets and odd-looking table contraptions

with moving needles and letter wheels. Clearly,

these early machines suffered from over engineering

if not lack of imagination. Called dial

plate instruments or psychographs, a few of

these devices appeared in the marketplace under

various names and incarnations.

The problem with table turning was that it

took far too long to spell out messages. Sitters

became bored when the novelty of a rocking table

wore off and the chore of interpreting knocks

began. Planchette writing was often difficult or

impossible to read. It was a challenge just keeping

the instrument centered on the paper long enough to

get a decipherable message. Consequently, many

mediums dispensed with the spiritual apparatuses

altogether, preferring to transmit from the spirit

world mentally in an altered state of consciousness

called "trance." Others eliminated the planchette

but kept the pencil, finding the hand a more

precise and less troublesome writing instrument.

But there were also those who felt it crucial to

use the right equipment if they were going to

contact the spirit world properly. These

resourceful individuals built weird alphanumeric

gadgets and odd-looking table contraptions

with moving needles and letter wheels. Clearly,

these early machines suffered from over engineering

if not lack of imagination. Called dial

plate instruments or psychographs, a few of

these devices appeared in the marketplace under

various names and incarnations.

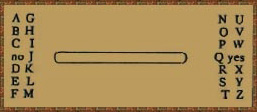

Exactly when the alphabet board with the detached message indicator came into use is unknown although it would have been early: "On another occasion, we happened to be on a visit at a house at which two ladies were staying, who worked the planchette on the original method (that of attaching to it a pointer, which indicated letters and figures on a card), and our long previous knowledge of whom placed them beyond all suspicion of anything but self-deception. One of them was a firm believer in the reality of her intercourse with the spirit-world; and her 'planchette' was continually at work beneath her hands, its index pointing to successive letters and figures on the card before it, just as if it had been that of a telegraph-dial acted on by galvanic communication." —Quarterly Review, October, 1871. Spiritualists freely communicated ideas with each other through the specialty magazines and bulletins of the time. "LK" had this bit of important information to share:

Many of your readers

may wish to communicate with their spirit friends,

but lack even that feeble mediumistic power which

is generally considered the first step to or

beginning of mediumistic development, viz: the

power to communicate by tippings of the table. But

there has been discovered, by my wife, a method

which will enable many persons to get

manifestations who could not get tippings of the

table; and for those who require tipping of the

table to point out the letters when the alphabet is

called, a method is here offered that will

facilitate operations greatly. My wife and myself

having discovered that we conjointly (not singly)

were able to have intercourse with our spirit

friends by tippings, found the process very

tedious; but soon as we tried the new method our

spirit son exclaimed: "Oh dear papa and mama you

have made our work so easy now." The method is

this: I have on the table painted the letters of

the alphabet, thus: On this table we place a

polished little rod, rounded below and pointed on

both ends; The upper side is wide for the fingers

to rest, and also rough so they do not glide off.

The table of course must be very smooth—I

facilitate operations by putting a little powdered

soap-stone on it. On this rod the fingers of the

two persons sitting on the opposite sides are

placed, and the rod is allowed to glide from letter

to letter. With this little arrangement we receive

messages now faster than by writing. If you think

this information useful, your readers are welcome

to it. Fraternally yours. LK —American

Spiritualist Magazine, December 18,

1876.

Many of your readers

may wish to communicate with their spirit friends,

but lack even that feeble mediumistic power which

is generally considered the first step to or

beginning of mediumistic development, viz: the

power to communicate by tippings of the table. But

there has been discovered, by my wife, a method

which will enable many persons to get

manifestations who could not get tippings of the

table; and for those who require tipping of the

table to point out the letters when the alphabet is

called, a method is here offered that will

facilitate operations greatly. My wife and myself

having discovered that we conjointly (not singly)

were able to have intercourse with our spirit

friends by tippings, found the process very

tedious; but soon as we tried the new method our

spirit son exclaimed: "Oh dear papa and mama you

have made our work so easy now." The method is

this: I have on the table painted the letters of

the alphabet, thus: On this table we place a

polished little rod, rounded below and pointed on

both ends; The upper side is wide for the fingers

to rest, and also rough so they do not glide off.

The table of course must be very smooth—I

facilitate operations by putting a little powdered

soap-stone on it. On this rod the fingers of the

two persons sitting on the opposite sides are

placed, and the rod is allowed to glide from letter

to letter. With this little arrangement we receive

messages now faster than by writing. If you think

this information useful, your readers are welcome

to it. Fraternally yours. LK —American

Spiritualist Magazine, December 18,

1876.

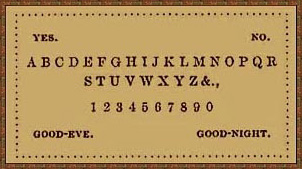

American and European toy companies actively peddled the planchette, making it immensely popular. The dial plate devices, although more sophisticated, were largely ignored. This was most likely because planchettes were easier to make and market inexpensively as novelties. Both took a back seat in 1886 when reports of an exciting new "talking board" sensation hit the newsstands. Mentioned in the March 28, 1886 Sunday supplement of the New York Tribune, the story quickly spread across the country. Here is a reprint of the Tribune article in an Oakland, California publication for Spiritualists, The Carrier Dove:

..............

A Mysterious Talking Board and Table.

..............

"Planchette

is simply nowhere," said a Western man at the Fifth

Avenue Hotel, "compared with the new scheme for

mysterious communication that is being used out in

Ohio. I know of whole communities that are wild

over the 'talking board,' as some of them call it.

I have never heard any name for it. But I have seen

and heard some of the most remarkable things about

its operations—things that seem to pass all human

comprehension or explanation."

"What is

the board like?"

"Give me a

pencil and I will show you. The first requisite is

the operating board. It may be rectangular, about

18 x 20 inches. It is inscribed like this: "The 'yes' and the

'no' are to start and stop the conversation. The

'good-evening' and 'good-night' are for courtesy.

Now a little table three or four inches high is

prepared with four legs. Any one can make the whole

apparatus in fifteen minutes with a jack-knife and

a marking brush. You take the board in your lap,

another person sitting down with you. You each

grasp the little table with the thumb and

forefinger at each corner next to you. Then the

question is asked, 'Are there any communications?'

Pretty soon you think the other person is pushing

the table. He thinks you are doing the same. But

the table moves around to 'yes' or 'no.' Then you

go on asking questions and the answers are spelled

out by the legs of the table resting on the letters

one after the other. Sometimes the table will cover

two letters with its feet, and then you hang on and

ask that the table will be moved from the wrong

letter, which is done. Some remarkable

conversations have been carried on until men have

become in a measure superstitious about it. I know

of a gentleman whose family became so interested in

playing with the witching thing that he burned it

up. The same night he started out of town on a

business trip. The members of his family looked for

the board and could not find it. They got a servant

to make them a new one. Then two of them sat down

and asked what had become of the other table. The

answer was spelled out, giving a name, 'Jack burned

it.' There are, of course, any number of

nonsensical and irrelevant answers spelled out, but

the workers pay little heed to them. If the answers

are relevant they talk them over with a

superstitious awe. One gentleman of my acquaintance

told me that he got a communication about a title

to some property from his dead brother, which was

of great value to him. It is curious, according to

those who have worked most with the new mystery,

that while two persons are holding the table a

third person, sitting in the same room some

distance away, may ask the questions without even

speaking them aloud, and the answers will show they

are intended for him. Again, answers will be

returned to the inquiries of one of the persons

operating when the other can get no answers at all.

In Youngstown, Canton, Warren, Tiffin, Mansfield,

Akron, Elyria, and a number of other places in Ohio

I heard that there was a perfect craze over the new

planchette. Its use and operation have taken the

place of card parties. Attempts are made to verify

statements that are made about living persons, and

in some instances they have succeeded so well as to

make the inquirers still more awe-stricken."—New

York Tribune.

"The 'yes' and the

'no' are to start and stop the conversation. The

'good-evening' and 'good-night' are for courtesy.

Now a little table three or four inches high is

prepared with four legs. Any one can make the whole

apparatus in fifteen minutes with a jack-knife and

a marking brush. You take the board in your lap,

another person sitting down with you. You each

grasp the little table with the thumb and

forefinger at each corner next to you. Then the

question is asked, 'Are there any communications?'

Pretty soon you think the other person is pushing

the table. He thinks you are doing the same. But

the table moves around to 'yes' or 'no.' Then you

go on asking questions and the answers are spelled

out by the legs of the table resting on the letters

one after the other. Sometimes the table will cover

two letters with its feet, and then you hang on and

ask that the table will be moved from the wrong

letter, which is done. Some remarkable

conversations have been carried on until men have

become in a measure superstitious about it. I know

of a gentleman whose family became so interested in

playing with the witching thing that he burned it

up. The same night he started out of town on a

business trip. The members of his family looked for

the board and could not find it. They got a servant

to make them a new one. Then two of them sat down

and asked what had become of the other table. The

answer was spelled out, giving a name, 'Jack burned

it.' There are, of course, any number of

nonsensical and irrelevant answers spelled out, but

the workers pay little heed to them. If the answers

are relevant they talk them over with a

superstitious awe. One gentleman of my acquaintance

told me that he got a communication about a title

to some property from his dead brother, which was

of great value to him. It is curious, according to

those who have worked most with the new mystery,

that while two persons are holding the table a

third person, sitting in the same room some

distance away, may ask the questions without even

speaking them aloud, and the answers will show they

are intended for him. Again, answers will be

returned to the inquiries of one of the persons

operating when the other can get no answers at all.

In Youngstown, Canton, Warren, Tiffin, Mansfield,

Akron, Elyria, and a number of other places in Ohio

I heard that there was a perfect craze over the new

planchette. Its use and operation have taken the

place of card parties. Attempts are made to verify

statements that are made about living persons, and

in some instances they have succeeded so well as to

make the inquirers still more awe-stricken."—New

York Tribune.

— Carrier Dove (Oakland) July, 1886: 171. Reprinted from the New York Daily Tribune, March 28, 1886: page 9, column 6. "The New 'Planchette.' A Mysterious Talking Board and Table Over Which Northern Ohio Is Agitated."

This was so amazing because this "new" message board was simple to make and required absolutely no understanding, skill, or mediumistic training to do—or so people were led to understand. When the message indicator "moved by itself" from letter to letter to spell out a message, it looked genuinely magical and astonishing. Maybe this was a new invention. But whose was it? Right about the same time, one of the nation's largest toy makers, W. S. Reed Toy Company of Leominster Massachusetts, put out a device strikingly similar to the "new planchette." Whether this new board was a reaction to or possibly responsible for the craze we can only guess. Dubbed the "witch board" it was described like this: "Upon the four corners of the board are respectively "Yes," "No," "Good-by" and "Good-day," while the alphabet occupies the centre of the board. A miniature standard, which rests upon four legs, stand upon the "witch board," upon which the hands are placed, and then the spirits begin their work. Should an answer be "Yes" or "No," the small table will travel to the respective corner, et cetera. Communications are spelled out by the diminutive table resting over such letters as may be wanted to spell out the message.—Boston Globe June 5, 1886

Reed's short-lived "witch board" might have been completely forgotten had it not been for an amusing incident. Charles S. Dresser, Reed's treasurer, sent President Grover Cleveland one as a wedding gift with the wish that "it may be of service." Whether Dresser might have been joking about the marriage is up for speculation. Frances Folsom was 27 years younger than the President and the age difference between the two had society atwitter. Cleveland replied with a courteous "I except it as an evidence of kind feelings and friendship, and can admire it for its ingenuity, but I hardly think that I shall immediately test its power to disclose the past and foretell the future."

Although Reed wouldn't trademark another similar item, the Espirito until 1891, other interested parties leapt aboard the talking board bandwagon within a few short years. The first patent for "improvements," filed on May 28, 1890 and granted on February 10, 1891, lists Elijah J. Bond as the inventor and the assignees as Charles W. Kennard and William H. A. Maupin of Baltimore, Maryland. Whether Bond or his Baltimore cronies knew about Reed's earlier "witch board" is, as the board might say, unclear, but there is no question that they were the first to heavily promote the board as a novelty.

Charles Kennard stated that he named the new board Ouija (pronounced wE-ja) after a session with Miss Peters, Elijah Bond's sister-in-law: "I remarked that we had not yet settled upon a name, and as the board had helped us in other ways, we would ask it to propose one. It spelled out O-U-I-J-A. When I asked the meaning of the word it said 'Good Luck.' Miss Peters there upon drew upon her neck a chain which had at the end a locket, on it a figure of a woman and at the top the word 'Ouija'. We asked her if she had thought of the name, and she said she had not. We then adopted the word. There were present Mr. Bond, his wife, his son, Miss Peters and myself." Kennard and Bond, doing business as Kennard Novelty Company, wasted no time advertising in local periodicals:

THE WONDER OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

This most interesting and mysterious Talking Board has awakened great curiosity wherever shown. It surpasses in its results second sight, mind reading or clairvoyance. It consists of a small table placed upon a large board containing the alphabet and numerals. By simply resting the fingers of two persons upon the small table, it moves, and to all intents and purposes becomes a living sensible thing giving intelligent answers to any questions that can be propounded. Wonderful as this may seem, the “Ouija” was thoroughly tested and the above facts demonstrated at the United States patent office before the patent was allowed. For sale by all first-class Toy Dealers and Stationers. Manufactured by The Kennard Novelty Company, 220 South Charles street, Baltimore, Md.—Baltimore Sun, December 6, 1890

Charles Kennard left the company after fourteen months to found Northwestern Toy Company in Chicago, Illinois. His ex-financial partners, headed by powerful Baltimore capitalist Washington Bowie, who was also manager, secretary, and treasurer of Kennard Novelty, continued the business under corporate control, then changed the name of the firm to Ouija Novelty Company. This didn't concern Kennard who made, as his flagship product, the Volo board—a Ouija replica. Bowie immediately filed suit for patent infringement forcing the end of the Volo along with a rather embarrassed apology from Northwestern to the trade. Unrepentant, Charles Kennard continued in real estate and other business ventures and produced one more talking board, the Igili, in 1897.

Perhaps Kennard's sense of entitlement came from his claim as inventor of the Ouija board. A series of letters to the Baltimore Sun in 1919, hotly discussed the issue. Kennard wrote that he was the sole inventor, having in 1886 (the year of the talking board craze) put together a crude board, using a cake board and a table with four legs and a pointer, marking in pencil the alphabet and numerals. Next to his office was a cabinetmaker by the name of E.C. Reiche who, at Kennard's request, made several copies of the board. Asked to make them in numbers for market, Reiche refused, complaining of a heavy workload. After shopping the idea around Baltimore and finding no takers, Kennard met Elijah Bond who made several improvements including the semi-circular alphabet pattern and the addition of felt cushions on the indicator legs, and had those improvements patented. Bond then joined with Kennard as manufacturers under the Kennard Novelty Company name.

Elijah Bond sided with Kennard but clarified that it was he, Bond, who had incorporated the company and had full control, he being the major stockholder. He called it Kennard Novelty out of “compliment to Mr. Kennard.” Bond also reported that he had gone to Washington with a lady (Helen Peters Nosworthy), a “strong medium,” and so impressed one of the chiefs of the patent office that the chief assured him then and there that the patent would be allowed. Similar patents in Canada, England, and France followed. Bond credited Kennard with having brought the Ouija to his attention and having the great energy and ability to make the board a success. After going to London and failing to successfully exploit his English patent in 1892, Bond was forced to sell his shares and relinquish his interest in the company.

Washington Bowie disputed Kennard on several counts. He said that the inventor of the Ouija was not Charles Kennard but Mr. E. C. Reiche, of Chestertown, Maryland. He further stated that Kennard Novelty paid Reiche in stock for "using his invention without compensation" and that this happened, not once but twice, Reiche being discontented with the first settlement. E. C. Reiche's son, W. Mack Reiche, backed Washington Bowie and allowed that although Kennard may have named the Ouija, he did not invent it. It was his opinion that Kennard never entertained the idea of such a device until it was shown to him in the home of Judge Joseph A. Wickes, Kennard's father-in-law. W. Mack Reiche was adamant that the Ouija "came into existence through the brains and hands of father alone."

Whatever the story, Washington Bowie remained the powerhouse behind the Ouija Novelty Company making most of the corporate decisions and installing his son, Washington Bowie Jr., as manager of the Chicago factory. Early on, he took 20 year old William Fuld under his wing and taught him everything he could about the business. Fuld rose quickly to position of foreman and became one of the original company stockholders. In 1897, Washington Bowie leased the rights to manufacture the Ouija board to William and his brother Isaac. With that single stroke of fate, William Fuld came to be the one history would forever remember as the father of the Ouija board.

William and Isaac Fuld embarked successfully

on their new venture and manufactured Ouija boards

in record numbers. Nevertheless, this business

partnership was not to last. Ouija Novelty’s

contract with the Fulds was for three years only.

At the end of this period, William formed his own

company—ended the partnership, and with that

Isaac’s rights to produce the Ouija board ended

also. A legal battle followed. The acrimony created

a bitter family feud that was to last for

generations. Isaac worked from his home workshop

where he produced and sold Ouija facsimiles, called

Oriole Talking Boards and

pool and smoking tables. Ouija Novelty collected

revenues on the Ouija name from William Fuld and

then in 1919 relinquished the remaining rights.

William sold millions of Ouija boards, toys, and

other games and kept a job as a US customs

inspector. Later in life he became a member of

Baltimore's General Assembly.

William and Isaac Fuld embarked successfully

on their new venture and manufactured Ouija boards

in record numbers. Nevertheless, this business

partnership was not to last. Ouija Novelty’s

contract with the Fulds was for three years only.

At the end of this period, William formed his own

company—ended the partnership, and with that

Isaac’s rights to produce the Ouija board ended

also. A legal battle followed. The acrimony created

a bitter family feud that was to last for

generations. Isaac worked from his home workshop

where he produced and sold Ouija facsimiles, called

Oriole Talking Boards and

pool and smoking tables. Ouija Novelty collected

revenues on the Ouija name from William Fuld and

then in 1919 relinquished the remaining rights.

William sold millions of Ouija boards, toys, and

other games and kept a job as a US customs

inspector. Later in life he became a member of

Baltimore's General Assembly.

For twenty-six years William Fuld ran the company through good times and bad. When interviewed about the Ouija he was amusingly frank. He was a Presbyterian, didn't believe that it was a medium of communication with departed spirits, but at the same time thought that the Ouija was a reliable advisor in matters of business and personal life. His explanation was that the board, through a type of magnetism or some kind of psychological phenomenon controlled the hands and led to the right answers. He offered personal anecdotes to illustrate. The board told him to "prepare for big business" and he did, building a new factory to support huge demands. When a large shipment consigned to St. Paul, Minnesota got lost, and a search by railroad officials failed to find it, Fuld asked the Ouija board and it directed him to Ohio, right where it had been misdirected. "The talking board named itself." He said. "We didn't know what to name it, so put the question up to the board and it spelled out O-U-I-J-A. We hadn't any idea what it meant and scratched a long time before we found any clue. Finally we discovered that it was a very close approximation of an Egyptian word which meant good luck." Although "inventor" was printed on the back of every board, William Fuld didn't claim to be the originator. He credited E. C. Reiche but said that he had been working on a similar board and had been beaten to the patent office.

In February 1927, William Fuld climbed to the roof of his Harford Street factory in Baltimore to supervise the replacement of a flagpole. A support post that he was holding gave way and he fell backwards to his death. Following his death, William's children took over and marketed many interesting Ouija versions of their own, including the rare and marvelous Art Deco Electric Mystifying Oracle. In 1966, they retired and sold the business to Parker Brothers. Parker Brothers produced an accurate Fuld reproduction and briefly even made a beautiful maple Deluxe Wooden Edition Ouija.

Almost from the beginning, William Fuld's Ouija board suffered fierce competition from other toy makers. Everyone wanted to make a variation of the Wonderful Talking Board. Ouija imitations with names like The Wireless Messenger and Ido Psycho Ideo Graph, flooded the market. Some companies, like J.M.Simmons and Morton E. Converse & Son even used the Ouija name and the identical board layout. Fuld responded with legal threats and by marketing a second, less expensive talking board, the Mystifying Oracle.

The 1940s saw a virtual cornucopia of artistic and colorful talking boards. Perhaps the most beautiful were Haskelite's Egyptian themed Mystic Boards and Mystic Trays. Other major players were two Chicago novelty companies, Gift Craft, and Lee Industries. Adorned with everything from wizards to cannibals, these talking boards were wonderful departures from Fuld's simple number boards. Gift Craft's popular Swami featured a flying carpet scene and a genii consulting a crystal ball. Lee's Magic Marvel, done in eye-catching red and yellow, had four turbaned soothsayers, the zodiac, and a couple of grumpy demons thrown in just for luck. Love them or not, no one could call them boring.

In early 1999, after thirty-three years, Parker Brothers stopped manufacturing the classic Fuld Ouija board and switched to a smaller less detailed glow in the dark version. Gone was the faux bird's eye maple lithograph and gone was the name William Fuld. Although some of us may morn its passing, we must remember the Parker Brothers slogan: "It's only a game—isn't it?"

Today, it may be accurate

to say that there is a renaissance afoot. Hasbro,

who currently owns Parker Brothers upped their game

in 2008 by introducing a controversial pink

version aimed at teen girls. Then in 2013, they

stunned everyone by breaking tradition completely

with a redesigned, much darker themed Ouija board

equipped with a light up planchette that

automagically illuminates hidden messages on the

board (see right). Still small by yesterday's Ouija

board's standards, it shows at least, that

imagination is not dead at Hasbro.

Today, it may be accurate

to say that there is a renaissance afoot. Hasbro,

who currently owns Parker Brothers upped their game

in 2008 by introducing a controversial pink

version aimed at teen girls. Then in 2013, they

stunned everyone by breaking tradition completely

with a redesigned, much darker themed Ouija board

equipped with a light up planchette that

automagically illuminates hidden messages on the

board (see right). Still small by yesterday's Ouija

board's standards, it shows at least, that

imagination is not dead at Hasbro.

Other manufacturers have also joined in with imaginatively styled, contemporary talking boards. Online auction sites allow artists, who formerly would not have had the opportunity, to display and sell their handcrafted creations to a worldwide audience. Talking board enthusiasts are creating websites, sponsoring public shows and events, and connecting with other collectors in an entirely new way. At this period in time, the Wonderful Talking Board has never been more popular.

See also: Ancient Ouija Boards: Fact or Fiction?

Ouija-stitions | Interactive | Books | Movies | Collect | Buy | Links | e-mail

Copyright © All Rights Reserved.